January 2017:

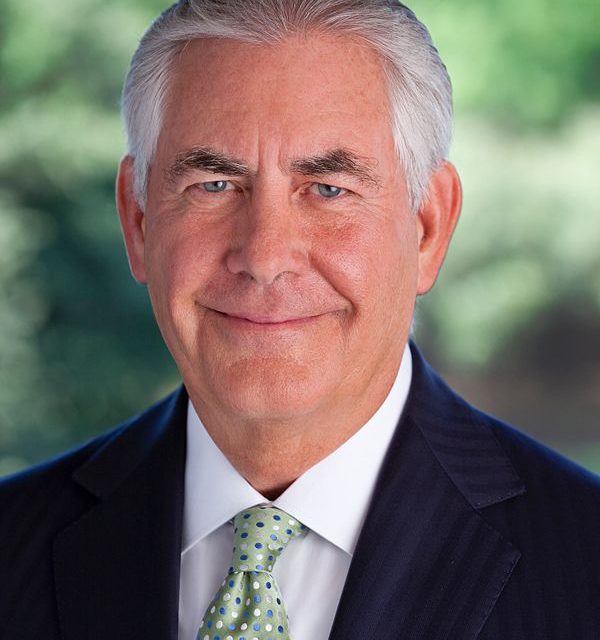

Donald J. Trump won the 2016 presidential election, in part, because he argued that his experience as a successful business person qualified him to become head of the federal government. And since his victory, Trump has announced his intentions to nominate more than half a dozen top business executives to run government departments. Most notably, Rex Tillerson, CEO of ExxonMobil, was chosen to be Secretary of State, while Andrew Puzder, CEO of the company that franchises the fast-food outlets Hardee’s and Carl’s Jr, was chosen to be Secretary of Labor. [Ed Note: Pudzer later withdrew from consideration].

What are the positives and negatives of appointing business leaders to run large government departments? On the one hand, successful business executives have shown the ability to master of getting better results from a large organization. This puts them in a good position to overcome the incentive problem: The potential lack of pressure on public sector managers because governments don’t need to make a profit.

On the other hand, in a market economy, the primary goal of business leaders is to maximize profits. By contrast, the goals of government are broader, including protecting consumer welfare, enforcing laws and regulation, and maintaining national security. So business leaders run the risk of being too narrow in their approach to running government departments.

It’s important to note that Trump is not the first president who has relied heavily on business executives to staff his administration. Dwight Eisenhower, a Republican who was elected as president in 1952, appointed former corporate lawyer John Foster Dulles as secretary of state, former steel magnate George Humphrey as treasury secretary, former CEO of General Motors Charles Wilson as defense secretary, and newspaper publisher Oveta Culp Hobby as secretary of health, education and welfare. The most notable exception was his Secretary of Labor, Martin P. Durkin, who was the former head of the plumbers’ and pipe fitters’ union. As a result, commentators referred to Eisenhower’s first cabinet as “Nine Millionaires and a Plumber.”

Eisenhower is remembered as a fairly successful and moderate president—in fact, a 2014 poll of presidential historians conducted by the Washington Post ranked him number 7 out of the nation’s 44 past presidents. Eisenhower oversaw sustained economic growth—averaging 2.5 percent of GDP per year—wound down the Korean War, and signed the Federal Aid Highway Bill of 1956 that ushered in our modern interstate highway system. He defended his corporate appointees as vital to improving government efficiency and effectiveness, writing in his diary that skeptics’ attacks on corporate leaders would lead to a situation in which “we will be unable to get anybody to take jobs in Washington except business failures, college professors, and New Deal lawyers.”

And it isn’t just Republicans who have relied on corporate executives. President John F. Kennedy, a Democrat, appointed Robert McNamara, who was president of Ford Motor Company, as his Secretary of Defense. McNamara, who made his reputation using statistical analysis to boost profits at Ford, was later blamed for helping lead the US into the disastrous Vietnam War by measuring success via statistics such as body counts rather than larger strategic objectives.

The McNamara example shows one of the pitfalls of appointing business leaders to run government departments. Business executives are trained to focus on the “bottom line”, the profits of the company. Shareholders and boards of directors hold executives directly accountable for the company’s performance. By contrast, government leaders must pay attention to a wider range of goals.

But critics also accused Eisenhower’s business executive-led administration of siding with business to the detriment of workers, including making it harder for workers to unionize. In fact, Labor Secretary Durkin, the aforementioned plumber, resigned after only eight months in office, citing his frustration with the president’s decision to adopt with what he believed were anti-union policies that favored big business.

As we consider Trump’s nominees and Trump himself, the key question is: Will they run the government like a business, or will he or she run the government for the sake of business?

By Adam Lerner

Note: This textbook-based blog is explicitly non-political. We analyze current events for the beginning economics students without imposing our own views on the topic.

Key Terms

Incentive problem: The potential lack of pressure on public sector managers because governments don’t need to make a profit.

Review Questions

Additional Readings

President Donald Trump’s Cabinet and Cabinet-level Nominees

Rosenzweig, Phil. “Robert S. McNamara and the evolution of modern management.” Harvard business review 88, no. 12 (2010).

“The Administration: The Pipe Fitter Disconnects.” Time Magazine Sept. 21, 1953.

Cohan, William D. “America’s New Dealmakers-in-Chief.” POLITICO Magazine Dec. 15, 2016.